The following is an edited transcript of a talk I recently gave at an internal conference regarding moderation ethics. Sensitive and insider information has been redacted.

Content Warning: this talk does include references to child exploitation, genocide, and racial and gender-based violence.

The Case of the Missing Videos

To get started, I want to talk about one of my favorite examples of moderation gone awry that I’ve seen while working in tech. During my time as a Product Expert, I received a ticket in which all videos on a customer’s website were suddenly and inexplicably broken. Their videos were their main lead generation source, and if you scrolled through their website, it was full of unsightly error messages. I couldn’t figure out what had happened. The error messages in the console were decidedly non-descriptive, so I sent the issue on to engineering to dig in deeper.

After the better part of the week, we got an answer. We weren’t the problem. The third-party video host was. The video host’s abuse detection systems flagged the customer’s account for distributing pornographic material, violating their terms of service. As a result, all of the videos in the customer’s account were blocked and unable to render.

If the customer was distributing pornography and pornography goes against the platform’s terms of service, then everything was working as designed, right?

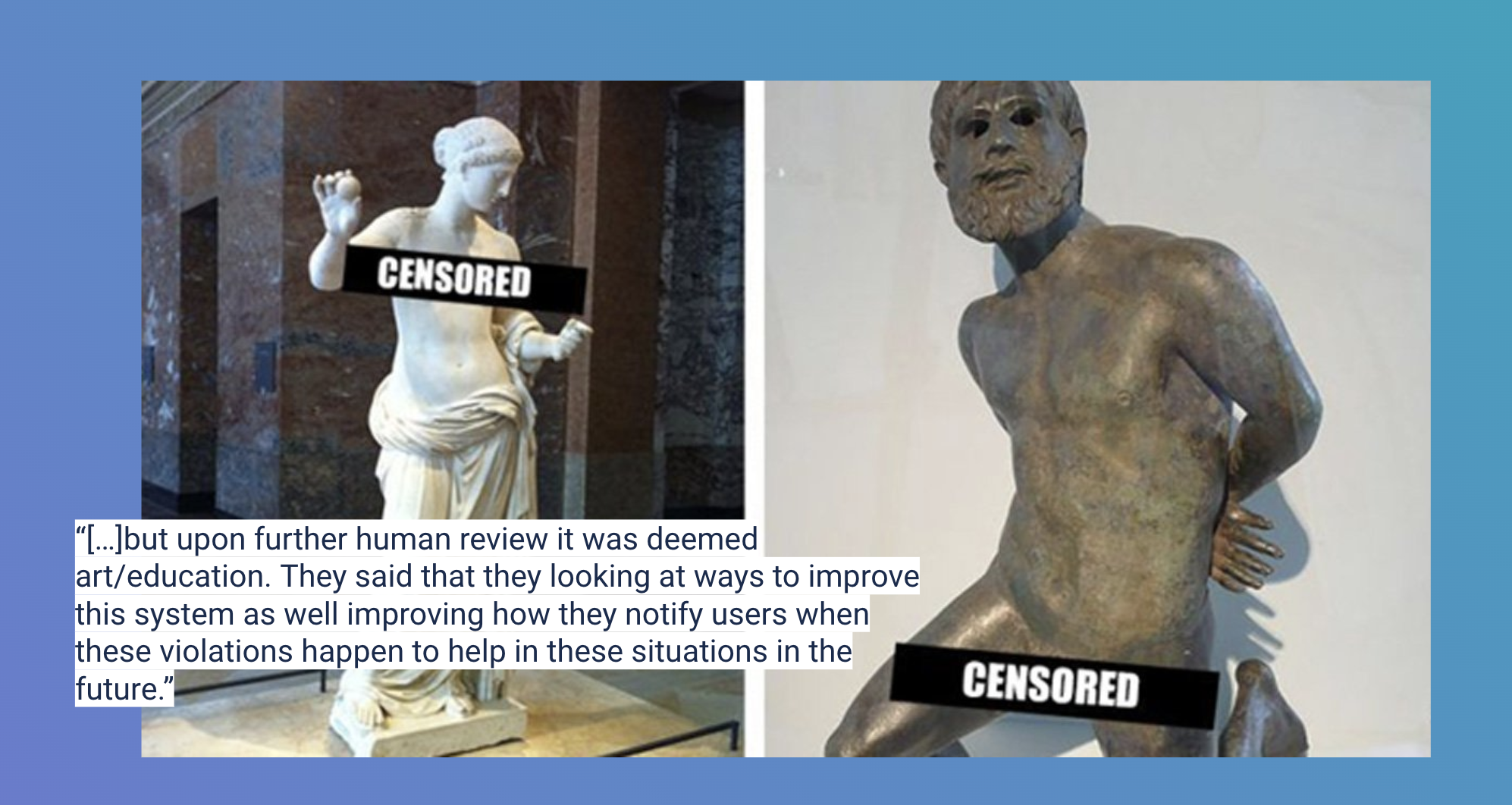

Well, not quite. The customer was an art museum. What the other platform detected were nude forms in paintings and statues. A single painted breast or carved phallus incorrectly categorized as pornography by a machine learning model and… poof. All videos were suddenly gone without warning or the chance to appeal the decision. It was painful for us to investigate and very painful for the customer, whose business this directly impacted. Ultimately, the other platform fixed the issue for the customer and restored their videos, but it wasn’t a quick or easy process.

I’m starting with this example because it’s ultimately fairly low stakes, but it illustrates some of the messiness of moderation that tech companies and platforms have to contend with.

Where Moderation Gets Messy

First, it demonstrates the role of bias in developing moderation policies: whose decision is it that pornography is inherently bad? Why is it bad? How do we distinguish artistic nudity like paintings from medical nudity like breast cancer screening graphics or pornographic nudity from political nudity, as in the free the nipple campaign? And does the distinction matter, too? These are all questions for which your personal biases and worldview will inform your answer.

Second, it helps us think about how business goals impact moderation. Going back to my first point, we can ask theoretical questions about whether or not nudity is worth moderating, but put yourself in the video host’s position for a moment. Suppose they’re wanting to scale in the B2B space. Do they want to deal with the contextual and cultural baggage of hosting pornography in the professional landscape of business solutions?

We have to ask ourselves if a platform associated with hosting pornography would also be trusted by businesses to host marketing assets, sales information, or customer service tools.

Third, it illustrates what may be the most important element of ethics and moderation: the importance of context and the limitations of algorithms to understand context. The AI model they used saw breasts, genitals, and butts and decided that if those elements were included, the content had to be pornography. Since their policies stated that pornography is bad, they enforced it according to the context the algorithms could understand.

Fourth, this example helps us frame some of the downstream impacts of moderation. For the customer, it meant lost leads and revenue. But what else? If we play a game of what-ifs, we can also see how even if things had gone differently, they might not be less complicated.

Who is Ultimately Responsible for Moderating Content?

For example, it’s easy to look at this example and assume that if the decision-making was not automated and relied on human review, a real person could have seen that it was an art museum and known that the content was okay. But there were dozens of hours of footage. Does that mean that a human has to watch dozens of hours of videos to determine whether or not a policy was violated? What if the videos were pornographic or, worse, included violent, non-consensual, or child exploitative content? Does that mean that a person has to watch each video in their account to confirm what they were dealing with before involving law enforcement? How does that theoretical employee deal with the stress and psychological dangers of exposure to that content?

Going in the opposite direction doesn’t necessarily make things less messy. You could say that it is the responsibility of the entity publishing the content– and not the platform being used to publish it– to self-censor. In fact, US law more or less endorses this approach through a piece of contested legislation known as Section 230 (yes, I am intentionally over-simplifying; no, I don’t have it in me to go in-depth on Section 230 today). Or, you could put the onus of responsibility on end users and viewers of that content to determine whether or not it is appropriate for themselves.

But if that’s the case, what happens to the platform when users distribute malware, phishing content, illegal content, or hate speech, and the platform’s shared domains and assets start getting blocked by browsers and security tools? What happens if a platform can see that a user’s content is directly causing harm and they choose to do nothing? For statues and paintings of nude figures, doing nothing is a valid choice. But what if the videos incited violence against a minority population, such as Facebook’s role in perpetuating pro-genocide propaganda against the Rohingya people in Myanmar? Or if those videos subjected individuals to targeted harassment, such as in the case of Twitter’s reluctance to get involved when Zoë Quinn was on the receiving end of death and rape threats during the GamerGate scandal?

In these cases, can being hands-off still be a valid option even though in matters of violence and oppression, a stance of neutrality is the conscious decision not to support the oppressed or vulnerable?

Regardless of the stance platforms take– to moderate or to not moderate– there is a tricky push and pull where you ultimately have to either accept the risk and responsibility of a non-interventionist approach or you have to clearly define parameters around what is and is not acceptable.

How Moderation Typically Functions in the SaaS Industry

What most SaaS and other tech platforms tend to default to is a harm-reduction approach to moderation. Most companies use proactive moderation mechanisms, such as automated scanning and machine learning models, to detect the kinds of content that are directly adversarial to users and are most likely to incur fines, service disruptions, or litigation. For example, things like fraud and phishing would fall into that category.

For other and more ambiguous forms of abuse, the default is to rely upon community policing models, which means that users and end users can report suspected abuse to the platform, which then investigates the report. Within SaaS, it is normal to be reactive rather than proactive for things like pornography and hate speech. These are more challenging for algorithms to understand comprehensively. For example, an algorithm may see white nationalists' hate speech the same as the Southern Poverty Law Center’s report on hate speech that cites the white nationalists’ words because it can’t understand the differences in the context in which it’s being used. This problem creates many false positives and inaccurate models, so we rely on reports and human reviews to help.

For some platforms, either an algorithmically detected piece of content or content that has received a critical mass of reporting will be automatically taken down. Still, in some cases, a human is involved in decision-making. This is sometimes referred to as a human-in-the-loop model, meaning that any time a piece of content is automatically flagged or manually reported, a human moderator will take a look and make the final decision. This is only sometimes feasible for platforms with massive bodies of user-generated content, or it results in moderating being outsourced en masse with minimal oversight.

In many ways, this approach to moderation makes a ton of sense. It allows us– as in, the collective SaaS industry us– to ruthlessly prioritize how we allocate resources to mitigate risk while creating a path forward for other types of harm we aren’t proactively seeking.

But this write-up is about the messiness of moderation ethics, not the straightforward, logical nature of moderation ethics.

Reactive moderation often comes up short because of how easily it can be abused. Plenty of social media platforms, for example, will automatically unpublish content once it hits a certain threshold of user reports, assuming that if users are actively reporting something as abusive, it has to be abusive. For companies the size of Meta or Bytedance, these reports may never be reviewed by a human unless the original poster appeals, assuming they have the resources to do so.

This sets the stage for moderation to be weaponized in the form of mass reporting or review bombing when relatively large populations of users are encouraged to report someone’s post or negatively review their public page. This exposes users to undue punitive measures by platforms– sometimes even to the extent that they lose access to the platform– for reasons that otherwise wouldn’t be restricted by the platform’s Acceptable Use Policy, such as political views or elements of their identity.

And if we dig into who often faces the most harm at the receiving end of these efforts, we see social power structures coming into play. Racial minorities, queer people, and women often face the most public backlash, and their content is also more likely to experience more punitive measures than other users.

For example, Richard Metzger, the former host of a television show on the UK’s Channel 4 called Disinformation, posted a photo on his official Facebook page of two men kissing. The photo was a still from the BBC soap opera EastEnders and was in response to an incident earlier that month in which two young gay men on a date were kicked out of a pub, seemingly for nothing more than being visibly gay in public.

Shortly after posting, his comments were full of aggressive and homophobic comments, and Within 24 hours of sharing the screenshot, Metzger’s post was taken down. In Metzger’s inbox was a warning that reads:

Content that you shared on Facebook has been removed because it violated Facebook’s Statement of Rights and Responsibilities. Shares that contain nudity, or any kind of graphic or sexually suggestive content, are not permitted on Facebook. This message serves as a warning. Additional violations may result in the termination of your account.

This is the photo in question.

According to Facebook’s documented policies, admins review all reports of abuse and terms of service violations, leading us to two terrifying conclusions. Either an administrator saw this photo from the reports and agreed it was graphic or sexually suggestive. Given that photos of couples kissing are not at all uncommon on Facebook, the only explanation for this determination would be because it features gay men and not a heterosexual couple. Or, it exposes that reports aren’t actually thoroughly vetted by a reviewer, leaving vulnerable and minority populations at risk of deplatforming due to targeted harassment. In both cases, moderation is ruled by individual bias rather than a uniform standard of acceptable use.

It’s easy to dunk on Meta for many reasons (stares directly into the camera). Still, across the industry, the role of bias in moderation is undeniable, and Meta isn’t the only guilty party when it comes to letting bias influence moderation. It affects what we choose to moderate, the decisions we make during moderation, and the tools we build and invest in to detect violations.

As a practice, moderation is a cycle of give and take. We’re constantly making trade-offs about what matters to us, our users, and the general public.

Competing Priorities, Budgets, and Legislation Muddy the Waters Further

When factoring in budget constraints, engineering constraints, and higher-order business goals, it would be dishonest to assert that a company can moderate against all forms of harm that could exist on its platform. We also have to ask if we want to do that in the first place.

Part of what makes moderation so contentious is that it ultimately determines who can leverage a platform for its intended use and who does not. If we’re over-eager with how we moderate, we run the risk of inadvertently causing material damage to our customers, such as in the earlier example of the video hosting provider taking down a customer’s primary acquisition channel. On top of that, there’s the risk of moderation being seen as a political weapon for silencing detractors, which can often happen when platforms are tasked with taking down things like misinformation or incitements of violence without being equipped to vet that content meaningfully.

This requires us to be selective and ruthlessly prioritize the moderation we pursue. If our goal is to prevent harm to our customers, business, and the general public, we have to contend with the fact that harm exists on a complicated spectrum of both types and severities. To limit the impact of personal bias, we do our best to thoughtfully quantify risk, considering whether a type of abuse can disrupt our services, could incur a financial loss for ourselves or customers, or would violate various laws and regulations. We also factor in other concrete data points, such as how many customers use a given feature, how readily available a feature can be accessed without vetting, and if there have been confirmed cases of abuse in the past.

Ultimately, my point is that we’re in a position where we have to make difficult moderation decisions. We have to say “no” or “not now” to really good ideas for us to ruthlessly prioritize the most impactful work we can do, which we interpret to be protecting the most people, both internally and externally, from the most direct forms of harm we encounter on our platform.

While that’s great for us today, we also have to look toward the future and ask ourselves what ethical moderation and policy development will look like as we scale and our customers become increasingly diverse and global. So, at this point, I’d like to pivot slightly and outline what I see as our guiding principles for continuing to develop our moderation ethos as a company.

- First, we must have a global view of customer needs. We have customers all over the world, and we will continue to expand into more and more countries as we scale. This requires us to be critical of how we develop policies and ask ourselves whether we are imposing US values on customers from other countries. This is still a relatively new muscle for us to flex, but it’s an important one and one that we’ve started figuring out how to use.

- Second, as we look to the future, we need to “Keep ethics in the spotlight and out of the compliance box.” I use quotes because I’m borrowing language from the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics. As I mentioned regarding predominant moderation frameworks, the industry favors risk mitigation that protects businesses and their customers from financial loss, litigation, and regulation non-compliance. This means that there is a gap in addressing where we’re thinking about ethics in a way that we’re positioned to do what’s right because it is right, even if there isn’t financial gain to be had in it or compliance forcing our hand. Resourcing and capacity constraints require us to prioritize ruthlessly, but product leaders must get comfortable asking ourselves and our stakeholders how best to protect our users and end users, even if it’s expensive, complicated, or unpopular.

- Third, we need to increase our internal and external transparency within the industry. One of the ways we can reduce our biases and protect our customer’s trust is to ensure that every user, regardless of the country they’re in or the languages they speak understands what is and is not allowed within your product. When people are told that they’ve broken the rules but were never told what rules they had to play by, it creates a feeling of unfairness and injustice.

Leaning into these guiding principles won’t be easy, but pursuing ethical moderation is always worth it. More than ever, customers and users care about their data security and the principles embodied by the platforms that they’re using. While content moderation is a necessary component of having a thriving user base, it can also do as much harm as good. When SaaS platforms root themselves in global inclusion, transparency, and user safety principles, however, we can decrease the risk of adverse consequences while building a healthier internet.